Making Hydrogen Work as a Fuel

Around 50 vessels have operated on hydrogen as fuel since the pioneering ferry Hydra set sail in 2000.

Whether it’s used in fuel cells or combustion engines, its capex and opex are still much higher than an equivalent diesel system, and it’s expected to stay that way until at least 2040.

But the real problem with using hydrogen as a fuel is that it takes more energy to make, compress/liquify, transport and store than it provides to a ship.

The expectation is that technology will come to the rescue. A study recently published in Energy Reviews explores using waste heat and latent thermal energy storage into all stages of the hydrogen value chain. This could boost electricity generation or reduce energy consumption by, for example, boosting passive cooling.

Will that change the equation for commercial shipping? Perhaps not, but there are still maritime projects pushing ahead with hydrogen fuel developments.

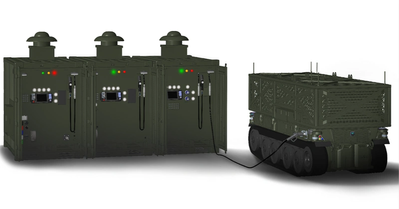

Late last month, the US Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) awarded Pratt Miller a contract to prototype their solution for the Expeditionary Hydrogen On Ship & Shore (EHOSS) project. The effort is designed to generate, store, and distribute hydrogen both aboard ship and ashore, creating a tactical micro hydrogen supply chain.

As a containerized hydrogen generation, storage, and dispensing system capable of providing more than 20 kilograms of 350 bar, the Pratt Miller system could provide high-purity hydrogen daily.

Energy usage includes fuel for both cell-powered unmanned systems and a lifting gas for high altitude balloons. This multipurpose approach supports disaggregated and expeditionary operations by providing lower acoustic and thermal signatures, extended range, and greater energy autonomy.

So, with a purpose beyond decarbonization, the DIU is overcoming the problems limiting hydrogen’s uptake in the commercial sector.